South Australian Blues Society

(It's the old 1999 website I have dragged out of the archives for you to have a look at!)

PETER GREEN

Martin Celmins. Chessington, Surrey: Castle Communications, 1995.

Peter Green is a name again in commercial blues after a period of about twenty years of comparative obscurity when he seemed to exist mainly as a legend or a myth. He was the guitarist who replaced Eric Clapton in John Mayall's Blues Breakers and who, with Mayall's rhythm section of the time, founded Fleetwood Mac, he was the man who dropped out of Fleetwood Mac at a time when the band was becoming increasingly successful (especially financially), the guitarist who I heard on more than one occasion had become a recluse, a mystic, a follower of Eastern religion, an alcoholic, and someone who had deliberately grown his fingernails so that he couldn't play.

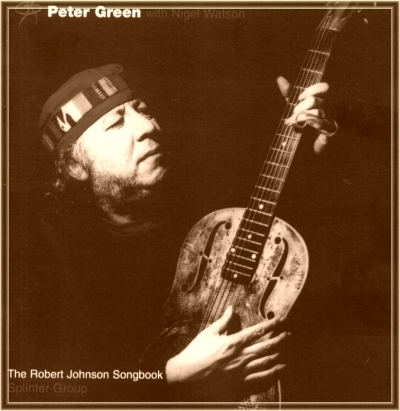

Anyone who likes blues and hasn't heard the 'Robert Johnson Songbook' is missing out on a treat.

Peter Green

This CD was released last year, in 1998. As well, Green has recently released a live album named 'Splinter Group' after his present line-up and a double CD called "Soho Session'. Given what I had heard - the gossip - I couldn't help asking myself why Green had decided, after a long period of absence from the limelight if not quite obscurity, to suddenly return to the international recording business - and for the matter why he had decided to drop out in the first place. I found some of the answers to my questions in Martin Celmin's recent biography of Peter Green.

Celmin's book is well worth reading. Because most of the people discussed in it are still alive it draws on a wealth of first-hand material. My major reservations with it relates to it's lack of analytic depth. The musical analysis is mostly restricted to the last chapter, which is the weakest in the book and Celmin makes too much of the effects of acid and mescaline in trying to understand the sudden change in the direction of Green's life. I am going to focus on the role of the blues in Green's life and how it may be related to the directions he took.

Green's grandparents came from Poland and the Ukraine, Ashkenazic Jews heading for the United States in the early part of the century, people who just happened to end up in London. One grandfather deserted his family and vanished into Eastern Europe never to return. The family name was Greenbaum until the family patriarch decided to change it to Green after the Second World War. Green's brothers report a significant amount of racial discrimination during their early years in London. A Jewish school friend of Greens did not know he was Jewish until after they had left school. In the 1970's Peter Green asked this man, Ed Spevock (bassist with Babe Ruth, Chicken Shack and The Peddlers at various times), to join him in an all Jewish band. At one stage during the 1980's, Green reverted to the name 'Greenbaum'.

He spent his teenage years as a fishmonger, a butcher's apprentice, and a French polisher of old television sets. He left school at 15 - a bright student who had lost interest. He got his first guitar at 12. Finding chords difficult he was however good at playing single notes and had a very good ear for music. The first song he learnt was 'Apache', by the Shadows - I have this much in common with Peter Green but I am afraid that - except for our hairlines - the similarities end there. He played in a Shadows-style trio with one of his brothers while at school.

One of his first professional bands, Shotgun Express, contained future Fleetwood Mac drummer, Mick Fleetwood - who remarked that when he first auditioned he did not think that Green was good enough to be in the band. People told him that he should try to play like John McLaughlin and other noted guitarists of the time but Green stuck rather stubbornly to his own style, mostly because that was all he could manage.

Success was rapid: He replaced Clapton in the Blues Breakers, became an internationally recognised virtuoso guitarist after the recording of 'A Hard Road' a few weeks later, and soon left Mayall's line-up to form his own blues band, Fleetwood Mac. 'Rumours' wasn't even a rumour at this time and the band's sound was very much like Mayall's with perhaps a greater emphasis on Elmore James coupled with a rock rhythm. Within a short space of time Carlos Santana had covered a Green composition called 'Black Magic Woman'. His own versions of his songs, 'Oh Well' and 'Albatross' became immediate international successes. The album,

"Peter Green's Fleetwood Mac" sold a thousand copies a day for several months after it's release in 1968, staying in the Top 10 for 'fifteen weeks and the album charts for a year'.

(p.65) Before he knew it, the life of a millionaire beckoned. Then Peter Green dropped out of the band.

An even of possible significance occurred one night when Green, who had become renowned for his on-stage bad language, was introducing the band. With John McVie's wife present in the audience, he said that McVie was so shy that it took him six months before he could even hold Christine Perfect's hand, "let alone f..k the arse off her". McVie was outraged and shouted over the microphone, "You f..king Jew!" (p.66) The matter was smoothed over but it's very occurrence may have been telling if not simply on it's own then as an occasion through which Green began to see the world differently.

Peter Green was an international star in his twenties but he still lived at home with his parents in a Jewish household – he was a musical celebrity one moment, and a working class son the next!

When a concert went badly his father wrote and publicly complained. One of Green's friends described his father as looking and behaving like Alf Garnet. At the same time band management was increasingly pursuing the commercial interests of Fleetwood Mac and old loyalties so much valued in a good Talmudic upbringing took second place. The rigorous schedule of nightly performances bought in the money but the old fun and adventure, the old magic was not so often there. 8

Part of Green's reason for leaving Fleetwood Mac was musical: "I had two parts to play," he complained on one occasion, "Because Jeremy wasn't going to make an effort to learn my things - to play properly on the piano. I was told he could play properly but I never saw him do that." (p.65) Green also wanted the drumming to sound more like the rhythm found on Jimmy Reed records. The introduction of his protege, Danny Kirwin into the line-up made the music even rockier, although Kirwin was a fine young blues guitarist. The President of the Fleetwood Mac fan-club had even bluntly told Green that 'Albatross' was a selling out of the blues.

But if the movement away from the blues had been part of the reason for Green's disillusionment, the way he - and the band - played the blues was just as much a cause. In 1969, during a tour of the United States, the band participated in a blues session at the Chess studios. Among the African-American musicians who participated were Elmore James' saxophonist, J.T. Brown, Buddy Guy, Willie Dixon, Otis Spann, Honeyboy Edwards, 'Shakey' Horton and S.P. Leary. Green said of these sessions:

"Those black guys knew that you can't get the hang of it - they knew that whatever a white guy tries to do is not going to be the blues of coloured people. It's a pose all along...I played too forcefully - too much and too loud - because my experience in life didn't match up to theirs. Perhaps white folks should've left those coloured tunes alone and stuck to singing hymns." (p.84)

McVie saw the situation slightly differently: "From the moment we arrived in the studio those guys made it quite clear that they didn't give a shit about who we were - we were just a bunch of white kids...I also got the feeling right from the start that Willie Dixon didn't care for me." (p.84-5) And Kirwin didn't mince his words about the session and the band's blues playing either: "Peter Green and me, we stole the black man's music. What we did was wrong." (p.85)

B.B. King noticed a change in Green from this time when he saw him a year later.

"In the studio he was quiet and I got the impression that he was very disillusioned with the whole music business." (p.89)

Green wanted to talk to him about religion and faith but King simply replied that Green's guitar playing had a sensitive touch. But then, at this time, Green regarded King's playing as 'Showbiz blues'. And Green no longer wanted to play with his own band either.

One day he appeared in the Melody Maker offices and demanded that they return all their photographs of him –

he did not want them appearing in newspapers. His views on life had changed. Green wanted to recover direct sensuous existence, to experience the high he got from drugs without taking anything. Some people suggested that he was becoming psychotic and, in a humble manner, he came to identify somewhat with the Messiah - but remember, he was a twenty-year old who suddenly had more money than he could have ever imagined. He wanted to give it away, not for altruistic reasons but because he hoped it would allow him to go back to being the person he was before he was successful.

Green applied to be a zoo keeper but lacked the qualifications, so he obtained a job as a gardener in a cemetery, employment that he liked and which gave him peace, but the music business would not leave him alone.

Fleetwood Mac needed him to fill in on a tour and during one concert he played a four-hour version of 'Black Magic Woman' in a total performance that went until four in the morning. Then he went to live on a kibbutz but found that he identified with the Palestinians and disliked the Israelis. He eventually gave away all his musical instruments and also started disposing of large sums of money. Celmins is somewhat vague about the details of the following event but seems that at this point Green's mother had him committed - although not even the medical fraternity could suppress a spirit which prevailed over a plethora of drugs and electro-convulsive therapy. It was a result of this treatment, I think, that he threatened some people's lives on one particular occasion and spent a period in Brixton Prison, followed by some more of those good old medical remedies. After a disastrous period in the early 1980's with a band called 'Kolors', Green stopped playing altogether.

This is essentially where Celmins' narrative ends but fortunately he is also the author of the sleeve-notes to the recent CD's, providing a useful 'latest instalment' in the life of Peter Green, blues musician. In 1995 he went to stay with Nigel Watson, a friend since the Fleetwood Mac days. When Green filled in on a tour with the band, Watson had accompanied him as the conga-player, and he and Green had also lived for a time in a forest, coming out only to purchase fast food when they got really hungry.

Green found that Watson was now playing Robert Johnson songs on a national steel guitar and using a fingerpicking style. Suddenly he heard the blues being played as he thought it ought to be played. Watson organised the Splinter Group and did the arrangements for the songs. I don't know if these arrangements would have pleased Willie Dixon and the boys but to my mind they certainly give expression to the blues of someone who has found that he can't be a Jew and also can't not be a Jew.

It would be cheap to call Peter Green the Django Reinhardt of blues music but the comparison is apt …

in at least one sense: regardless of their skin-colour, no-one would seriously argue that Django Reinhardt could not play swing. Green's character as a blues player is epitomised in a remark he makes on the live Splinter Group album. He describes how when he took over from Clapton, the Blues Breakers had played a Freddie King instrumental called 'Hideaway'. Required to come up with something similar from King's repertoire, Green remarks that 'I did this one called "The Stumble" - and I'm still trying to get it right'.

Everlovin' Trev.